Carving Shapes from Imagination

“The playground, instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there), becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play. And it is a thing of beauty as the modern artist has found beauty in the modern world.” Isamu Noguchi (1967).

Isamu Noguchi, an American artist, furniture designer, and landscape architect, developed his outdoor playgrounds to promote creative interaction as a means of learning (Noguchi Playscapes, 2017). Noguchi claimed that children’s play in public settings could facilitate their active engagement in society. The landscapes created by Noguchi served as contemplative spaces that prompted reflection on profound inquiries regarding space, time, and humanity’s existence. Noguchi consistently maintained an open mindset and tuned in to his inner voice. It implored him to reestablish ties with his roots, apply diligence, and persevere resolutely. Ultimately, it urged him to dismiss the limitations imposed by society and adopt those dictated by his vision.

Throughout his prolific six-decade career, Isamu Noguchi explored nearly every artistic medium accessible to him. Noguchi used drawings, models, and collages to construct his biomorphic interlocking sculptures during the mid-1940s. They were delineated and excised from black construction paper. The elements were built into small, independent models. The composition was observable from all angles, the model shapes were altered using scissors, and physical stability was assessed. Later, Noguchi scaled up his cut-outs and created slender, flat slabs of slate or marble. He employed a circular saw to carve and bevel the larger forms on the stone surface in accordance with their penciled outlines. His notched interlocking sculptures can be constructed without fasteners or supports.

To comprehend life forms and to establish a morphology, whether for scientific, artistic, or other objectives, is it sufficient to replicate the prompt data acquired from our acute awareness?

In the 1930s, biomorphism represented a prominent movement in art and sculpture, observed across various schools of thought in the 20th century. This method involves developing abstract shapes that evoke the natural world. This style indicates a balance between mathematical abstraction and an entirely figurative approach to art. Biomorphism and mathematics can mutually enhance each other through the exploration of complex subjects such as topology, fractals, dynamic systems, and catastrophes, extending beyond fundamental geometry. The 1930s marked a pivotal moment for biomorphism in art and sculpture, as this movement emerged as a significant force that seamlessly intertwined abstract forms with references to the natural world. By balancing mathematical abstraction with figurative approaches, artists of this era pioneered innovative expressions that not only celebrated organic shapes but also engaged deeply with complex subjects such as topology, fractals, dynamic systems, and catastrophes. This synthesis of ideas enriched the artistic landscape, demonstrating how the exploration of seemingly disparate concepts can lead to a profound understanding of both nature and abstraction. Biomorphism from the 1930s serves as a testament to art’s ability to reflect and engage with the intricacies of existence itself.

Often referred to as a “welded steel assemblage of geometric and biomorphic forms,” Louise Nevelson’s Summer Night Tree is a monumental abstract sculpture characterized by substantial, flat, twisting, leaf-like structures emerging from a slender trunk-like cluster. The uniform darkness and geometric designs are foreboding. Circles, squares, and crescents possess significant connotations. Circles symbolize completeness and life cycles, squares denote stability and the earth, while crescents embody lunar and feminine energy. It is remarkable how Nevelson deconstructs elements.

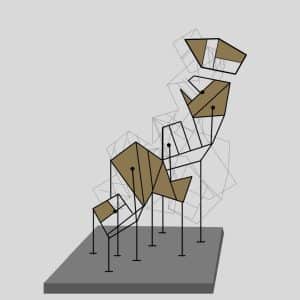

In the Erdman Hall project, architect Anne Tyng introduced an intricate “molecular scheme,” in which the planimetric concept of alternating altered planes is transformed into three dimensions through the interpenetration of spaces. The apparent simplicity of the two-dimensional illustrations reveals a complex comprehension of space that requires investigation through the theoretical and material remnants preserved by Tyng herself. This complexity may be interpreted as a conceptual tessellation of numerous solid geometries, culminating in an architectural design where specific features, consistent with wayfinding principles, are discernible, as exemplified by the clustered corridor layout. Tyng’s aim to explore the importance of geometric structures in their transformation into architectural forms is commendable and occasionally yields diverse interpretations. Tyng recognized the need to provide a variety of configurations for house entrance doors, rather than only differentiating them by color or other ancillary attributes. She conducted an in-depth study of regular geometries and proportions, resulting in multiple original geometric drawings that were not exclusively architectural. Tyng conceived The Toy, a modular, interlocking construction set, in 1948, before her licensing. Children may assemble a rocking horse or a little vehicle using 21 components. Geometric intricacy captivated Tyng throughout her life. She was in a relationship with architect Louis Kahn and contributed to the design of Philadelphia’s unconstructed City Tower. The tower’s geometric design draws inspiration from The Toy. Kahn’s architectural designs incorporate Tyng’s toys. This collaboration between art and architecture reflected their shared passion for innovative forms and structures. Tyng’s influence on Kahn’s work not only showcased her creative vision but also highlighted the enduring connection between play and design.

Design is, inherently, a creative pursuit. Architects envision entities that are not yet realized; they anticipate the future. Creativity is fundamental to envisioning the possible development of spatial conditions and cultivating ideas about future opportunities. Literary authors create worlds that offer innovative viewpoints and stimulate reflection on imaginary possibilities. Artists, including Noguchi, Tyng, and Nevelson, aimed to comprehend and employ the techniques through which architecture defines and molds space. An architect or sculptor’s primary responsibility may be to synthesize various disciplines, methodologies, and practices with the creative exploration of alternative possibilities.